FIVE YEARS AFTER THE DEVASTATING CAMP FIRE, A SMALL TOWN RALLIES TOGETHER, RISING FROM THE ASHES A BETTER, MORE RESILIENT COMMUNITY

Story by Mike Flenniken | Photos by Geoff Bilau

Just over five years ago, the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California history roared through Butte County in Northern California. The Camp Fire, which started the morning of Nov. 8, 2018, because of a faulty electric transmission line, burned more than 153,000 acres, led to 85 deaths and destroyed nearly 19,000 structures, more than 10,000 of them homes. Paradise, a town about 90 miles north of the state capital of Sacramento, lost about 95 percent of its structures.

Official magazine recently visited Paradise to speak with four people who are playing key roles in the rebuilding effort, two of whom lost their homes. There’s no instruction manual for putting a town back together, so the effort truly requires a combination of teamwork, innovation and determination.

Evidence of the fire’s destruction is still visible throughout the town, as shopping centers once brimming with people now sit empty, faded signs beckoning shoppers to empty parking lots and vacant fields. Parcels of land where houses stood remain abandoned, their owners either waiting to rebuild or having decided to move out of town.

There are also plenty of signs that Paradise is on the road to recovery. The town is bustling with construction, and the rebuilding effort includes an emphasis on fire-safe buildings and plans to decrease the odds of a similar disaster occurring again.

Paradise Building Official and Fire Marshal Tony Lindsey is among those whose families were displaced when the fire destroyed their home. Lindsey spent the day providing updates to the Emergency Operations Center and, using garden hoses, fought spot fires around town hall with the fire chief until an engine company arrived.

“They did more structural protection, because if we had lost all those documents, it would have been much harder to rebuild.”

Tony Lindsey is the building official and fire marshal for the town of Paradise.

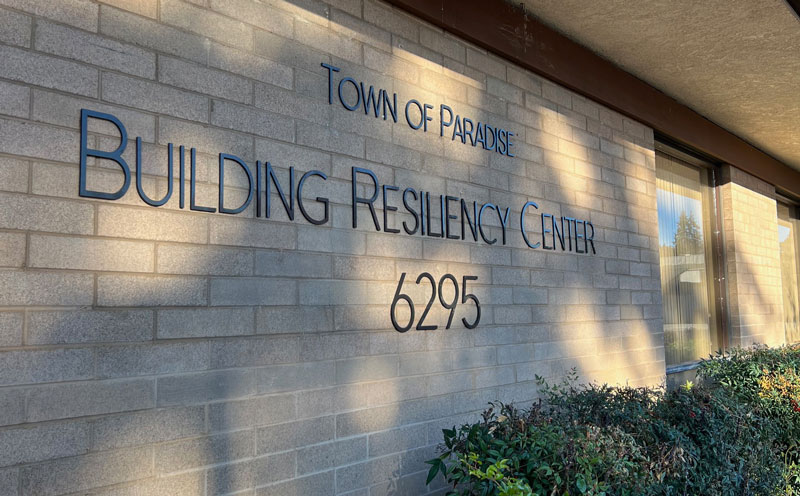

The Building Resiliency Center houses Paradise’s wastewater, building, fire prevention, planning and code enforcement departments.

As he worked tirelessly to evacuate the town and save town hall, the place he and his family had called home since 2011 went up in flames. Because he had raced to Paradise from his office in Chico, he was still in his dress shoes.

Originally from Michigan, Lindsey followed his wife to California for a career opportunity in 2004. They moved just outside of Paradise in 2006 and had been in their home since 2011. While they were able to grab their most important items, most of their possessions were gone.

“All your childhood stuff that you just had, all that stuff,” he said. “Christmas ornaments, whatever. All burnt. You had what you had, and luckily, I had a gym bag with a couple things and a change of clothes in my office down below. But of course, you forget, everything we had put on the hard drive? We forgot the hard drive. Luckily, we had our birth certificates, got all those kinds of important documents.”

Though it was understandably tempting, Lindsey waited to inspect the damage to his house until the rest of the community was able to do so as well.

“Even though I was up here and had plenty of opportunity to do so, I just didn’t feel it was right until everyone else could actually do the same thing,” he said. Lindsey was the Community Development director for the city of Chico, about 15 miles west of Paradise, at the time of the fire after working for Paradise from 2010 to 2017.

In 2020 he returned to help oversee the rebuilding efforts.

The town set up a one-stop shop for development, the Building Resiliency Center (BRC), to co-locate the wastewater, building, fire prevention, planning, and code enforcement staffs in the same building. Bank of America donated the facility to the town.

“The BRC takes care of all the permitting and the rebuilding in Paradise,” he said.

Lindsey said the town’s population, which was about 26,000 before the fire, is just under 10,000 now but steadily increasing.

He said his office has received 3,031 permit applications for single-family homes, has granted 2,820, and has issued 2,160 certificates of occupancy. For multifamily units, there have been 777 applications, 591 permits issued and 434 certificates of occupancy. They’re issuing about 30 permits each month.

“We’re maintaining that, even with such impediments as higher interest and insurance rates, COVID and work force shortages, but they’re more toward a smaller version of homes, like on average about 1,500 square feet, which was really the meat and potatoes of Paradise,” he said, adding that the percentage of manufactured homes has dropped from 30 percent pre-fire to about 28 percent.

Fire prevention is a key focus of the rebuilding effort, and the town is partnering with the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS) to make all homes eligible to be certified as Wildfire Prepared.

He said insurance companies are starting to require the certification to renew policies for some homes.

“IBHS is really focusing on the building envelope, the hazard ignition zone around the home, with the first five feet required to be non-combustible, including fences,” he said. “That has certainly helped, and we’re really focusing on defensible space.”

SEWER SYSTEM

Paradise is the largest unsewered community west of the Mississippi. A standard residential septic system in the community consists of a 1,500-gallon tank and a leach field. Plans to increase a home’s size must include a larger system as well. However, that is scheduled to change soon.

According to the Town Council, the proposed $233 million Paradise Sewer Project would include core collection, export pipeline and extended collection systems. Gravity sewers, pump stations and pressure pipelines would collect wastewater from the service area and convey it to the export pipeline system at the town’s southwestern edge. An 18-mile pipeline would take that wastewater to the Chico Water Pollution Control Plant. The extended system would allow for collection of sewage from parcels that are within Paradise but outside of the core system until it reaches capacity.

Final design, right-of-way acquisition, permitting and approvals are expected to be completed by summer, when construction would begin. Plans call for the export system to be finished in winter 2026 and the core system that summer.

Paradise Irrigation District Engineer Blaine Allen said the town’s new reservoirs are more fire safe than the previous one, which was damaged in the Camp Fire.

Lindsey’s work truck parked at the entrance to one of the manufactured home parks that was wiped away by the wildfires and hasn’t yet returned.

RESTORING WATER SERVICE

Paradise is served by Paradise Irrigation District. The district draws all of its water from Paradise Lake and the Magalia Reservoir, and its water treatment plant is north of town. The district is steadily restoring the infrastructure to make sure the town has clean and safe water.

The district serves the town with a gravity-based water system that has seven different zones, which Lindsey said can be challenging when designing fire sprinklers for every new home because they must make sure there is enough pressure and volume.

A 3-million-gallon reservoir that was damaged in the fire was already scheduled to be replaced; in fact, a bid meeting was scheduled for Nov. 9. The reservoir has been offline since the fire and is being replaced by two 1.5-million-gallon structures that are due to go online soon.

“It’s going to be the same capacity, just a different storage version and a little more fire safe,” Paradise Irrigation District Engineer Blaine Allen said.

In addition to replacing thousands of service laterals they are installing fire-safe meters that do not have the same plastic exterior components as the previous ones. This has been difficult, he said, because they don’t always know where everything was located because so much was destroyed.

“They were taken out during the process of clearing the land, so we have to go find those old lines and cap them off or reconnect them so we don’t have too many connections in our pipeline,” Allen said.

The district now requires backflow preventers at every connection due to contamination that occurred during the fire. Because that means each home will now have a closed-loop system, an expansion tank will be required on all tank hot water heaters.

Two 1.5-million-gallon water reservoirs are due to go online soon.

A worker puts the finishing touches on a reservoir’s roof.

“We’ve had to educate our community in that regard about closed systems, because not everybody is used to having backflows on every home,” Lindsey said. “That was a little bit of a challenge, to educate them and get our industry staffers and workforce educated.”

Allen said the number of water lines that remained open during the firefighting effort led to a major decompression event that damaged service laterals and caused contamination. They are now going through and replacing those service laterals.

They also ran an extensive water testing program to determine which water mains needed to be shut off. This included making sure homes that survived the fire did not have any contamination in their lines, and main lines that showed signs of contamination even after flushing will be replaced.

The town also expects to have all its roads repaved by the end of 2025, and all utilities will be underground. The district is working with the town to install the water lines before all the roads are repaved.

Ross Dress for Less and Tractor Supply Co. stores recently opened in Paradise.

A shopping center directory sign is all that remains of the Old Town Plaza, which was destroyed in the fire. Tenants included a Safeway, a Grocery Outlet and a Round Table Pizza.

“They’re really good to work with,” he said. “We try our best to coordinate on everything so we can give the best possible product from both of us for the citizens of Paradise.”

On the commercial side, Lindsey said it’s a “chicken-and-egg” situation in which businesses are seemingly waiting for the population to increase before returning, while potential residents would like to see more businesses before they come back. The town still only has one grocery store because the Safeway shopping center burned down, and fast-food offerings remain limited. However, a Tractor Supply Co., which was not there before the fire, recently opened, as have Big Lots, Ross Dress for Less and True Value Hardware stores.

DEALING WITH COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic, which began a little more than a year into the recovery effort, also took its toll on Paradise. Lindsey said quarantine plans were implemented immediately, and they took steps to make sure employees were safeguarded against the virus coming in.

“We were essential personnel,” he said. “We still had to maintain all our services here. Inspectors were still in the field; we still had to take plans in and deal with the public.”

Employees and contractors’ crews experienced staffing shortages, hindering the rebuilding process, as well as supply chain shortages that it brought about.

Right: Empty mailboxes that used to serve residents of the now-closed Ridgewood Mobile Home Park.

“Doors, windows, everything you need to really complete your home, were unavailable,” he said. “ABS, plastics, PVC; those were hard to come by as well, and that really spiked up prices. When you’re building a smaller home and all of a sudden you have $10,000 more in your lumber package, that hurts because you don’t have infinite funds.”

The town and charitable foundations stepped in to help whenever possible as well. NFL quarterback Aaron Rodgers, a Butte County native, partnered with the North Valley Community Foundation to establish the Aaron Rodgers NorCal Fire Recovery Fund, which helped fund housing initiatives as well as youth recreational programs.

Another nonprofit, Rebuild Paradise Foundation, offered grants to help with septic systems that were damaged in the fire.

The increase in permit applications brings with it an increase in inspections. Before the fire, Paradise had one inspector on staff, and initially hired contractors to perform the additional inspections. Lindsey said the council then gave his office the go-ahead to hire additional inspectors.

“Wherever you look, everybody’s short on staff,” he said. “Our Town Council approved three full-time inspectors and two part-time inspectors, and we were able to recruit and hire.”

Lindsey said that while they are combination inspectors — plumbing, mechanical and electrical — each still has a specialty. For example, one only performs final inspections on homes because that can often fill up a day, two focus on wastewater and another two specialize in fire prevention. He said one of the part-timers focuses on the simpler inspections so the full-timers can handle those that are more technical. This often allows them to return in the afternoon to reinspect a property that may have failed in the morning.

Recovery and Economic Development Director Colette Curtis said the town has worked closely with FEMA to get funding for tree removal on private and public property.

Work continues on an apartment complex behind Paradise High School. Lindsey said the town is seeing an increase in multifamily construction.

WORKING WITH FEMA

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has played a major role in the rebuilding effort, and Recovery and Economic Development Director Colette Curtis has served as the liaison.

She said FEMA offers two types of funding: public assistance and hazard mitigation program grant assistance. The first type is to immediately repair damaged suffered during a disaster, such as a burned-out culvert or a tree that may have fallen across a roadway.

Hazard mitigation, meanwhile, is more forward looking, and includes such projects as early warning sirens.

“That is money that’s eligible to communities that have been through a disaster and are looking to make their communities more sustainable and resilient in the future to mitigate against future disasters,” she said.

“We have had both types of funding.”

Curtis said hazard tree removal has fallen into both categories, and that Paradise had to be somewhat creative because FEMA does not typically fund tree removal on private property.

“In this disaster, we really made the case that not funding tree removal on private property is a huge barrier to recovery, and so we actually got them to change their minds and create a first-of-its-kind program through public assistance to remove trees that are on private property that could fall onto a public roadway.”

Although FEMA would not initially cover trees on private property that could fall onto private property, like a home or a business, Paradise still made the case that those are important to remove and applied for funding through the hazard mitigation program to do so. Curtis said that program is ongoing.

Curtis said there have been no impediments to receiving FEMA funding based on the codes the town utilizes in its construction practices. She said other than how long the process has taken, the biggest issue came when the town initially told residents they could set up a trailer or RV on their property if it was at least 30 feet from debris, but FEMA said that would contradict the town’s claim that it was a health and safety hazard.

“We had to kind of come back and say, ‘Sorry, you cannot go back on your property until the debris has been removed. Once the debris is removed on your property, you can go back even if your neighbors haven’t.’ So that was a way that we shifted. It was all very frustrating.”

Paradise will also use FEMA hazard mitigation funding for its Residential Ignition Resistant Improvement Program to update homes that survived the fire and make them safer and more fire resistant.

Curtis, whose home between Paradise and Chico survived the fire, said she has been encouraged by how well the rebuilding effort has gone.

“I think we all were really stunned and shocked right after the fire and didn’t know what was going to happen,” she said, “but this community has come together and worked so hard, and I think we are recovering at a faster rate than we ever expected.”

WEARING TWO HATS

Longtime Paradise resident Greg Bolin has been involved in the rebuilding effort from two perspectives: not only as mayor, but as president of Trilogy Construction, Inc., which owns two office complexes; one of them had about 20,000 square feet damaged—including their office — and the other emerged unscathed. For the latter complex, although all 25,000 square feet had been rented out prior to the fire, nobody wanted to stay.

“Everybody just left, I said, ‘Where are you going?’ They said, ‘We’re leaving; you’re going to have to sue us if you want anything.’ So that made it tough for that part of it.”

Bolin said everybody in the office lost their homes, so the first order of business was figuring out where everybody would live in the short term.

“Once we got our feet on the ground and got going, we’ve been very busy. As horrible as it’s been, it’s been tremendous to be able to get people back in their homes,” he said. “That part has been very rewarding and I’m very thankful for that, but it’s been a tough five years. You’re just tired. You put your head down and go, and just try not to think about it; just move, just do what you have to do.”

For Bolin, this was the second time his house had burned. Six months after moving into the house in 1991 — three days before Christmas — his family lost most of their house in a flue fire that started in the chimney. He said even though his wife wanted to rebuild in that same location, he couldn’t stomach the thought of doing it a third time. They eventually sold that property and rebuilt on a parcel of land that overlooks the canyon. He said such scenarios are not uncommon.

“That’s been the hardest thing for people. Some wanted to come back, some didn’t,” he said. “Most couples are not together on that, so that was very difficult.”

Bolin said Paradise is essentially an 18-square-mile job site with about 4,300 people coming up every day to work, whether on homes, underground or roads. He said while he is used to large worksites, having built projects in Sacramento, the Bay Area and Reno, Nevada, this was different.

“I’m used to it, but not this big,” he said.

Bolin began his term as mayor in December 2022 after more than a decade on the Town Council. He said there were discussions about the need to thin out the forest before the fire, with some saying the thick forests were what gave Paradise its beauty while others said they were its big problem.

Where there were once thick forests on either side of roads throughout the town are now views of canyons. For some, it is reminiscent of how the town looked in their youth.

“It’s interesting because the old-timers who have lived here since the ’30s — born here, in the ’30s, ’20s — didn’t seem to be knocked off their game with this,” he said. “All these people who have been here for almost a century, been here for decades since they were born, said this is just like it was when we were kids.”

Bolin predicted the sewer system will be a game changer in terms of attracting businesses, as those that have come in were in complexes that survived the fire so engineered septic systems were already in place.

SLOWLY BUT SURELY

A Paradise resident since moving from Los Angeles at the age of 9, Bolin said the town has always been a group of “leave-me-alone type of people” who created a tight-knit community in which everywhere you go you would run into people you knew.

“After the fire you lost that for a little bit, but that’s coming back now again. It’s a small-town feel; smaller than it was before, but very quaint, and it’s getting the momentum of people coming back home and people excited about being here,” he said.

Allen grew up in Chico but lived in Texas for 10 years before coming to work for the Paradise Irrigation District a couple years ago. He said it is one of the most challenging jobs he’s ever had because there’s something new every day.

“There’s no book for it,” he said. “I used to design mobile oil rigs. Well, they’ve been designed for 100 years. You can look back and see all this. There’s no, ‘Well, here’s another town that burned down to go look at and learn whom we should prioritize and how we should do things.”

While he readily admits he didn’t entirely know what he was getting himself into when he joined PID, he said it’s great to be part of the rebuilding process.

“I really like having a job where I can see that I’m helping people out,” he said. “It’’s gone pretty far in five years. We appreciate every one of our customers that have stuck with us; without them we wouldn’t be here.”

Lindsey said before the fire, Paradise had the vibe of an old gold-mining town. While those roots remain through such celebrations as Gold Nugget Days and Johnny Appleseed Days, the town is becoming more of a modern community. Paradise remains family oriented, as evident by the higher-than-expected enrollment in its schools, some of which sustained damage.

Although Lindsey and his wife ultimately moved to Chico, where she works, they remain active in Paradise’s local community and still attend church in the town he is helping rebuild.

“Here you’re a part of something; you’re rebuilding a town,” Lindsey said. “It’s a real calling.”

Mike Flenniken

Mike Flenniken is a staff writer, Marketing and Communications, for IAPMO. Prior to joining IAPMO in 2010, Flenniken worked in public relations for a group of Southern California hospitals and as a journalist in writing and editing capacities for various Southern California daily newspapers.

Last modified: March 20, 2024