HONOLULU DEPARTMENT OF PLANNING AND PERMITTING WORKS WITH ISLAND CONTRACTORS AND LOCAL LEADERS TO PROMOTE RESILIENCE FOR OAHU’S FUTURE

Honolulu may be famous for its iconic beaches, lush landscapes, and aloha spirit, but like much of the Pacific region, it faces increasing pressure on its natural resources. As drought conditions become more frequent across the Hawaiian Islands, the city is taking proactive steps to manage water more sustainably and build resilience into its infrastructure. With a population of nearly 1 million on O‘ahu and limited freshwater sources, efficient water use is not just a priority — it’s a necessity.

The largest city and home to Hawaii’s capital and busiest airport, Honolulu serves as the primary gateway to the state’s thriving tourism industry. Welcoming millions of visitors each year, the city plays a central role in an economic sector that generates more than $10 billion annually for the local economy.

With climate change bringing more frequent droughts and reduced rainfall, city leaders have committed to protecting this resource through targeted conservation measures. These include mandatory water-efficient plumbing fixtures in new construction, expanded use of recycled water for irrigation, and adoption of sustainable building practices through strict adherence to updated plumbing and mechanical codes. Honolulu also works closely with the Board of Water Supply to promote water conservation island-wide, reinforcing the critical connection between urban development and environmental stewardship.

The Department of Planning and Permitting (DPP) oversees these efforts through its Building Division. Clayton Oku, who is head of the Mechanical Code Branch, plays a key role in this work. His team of mechanical engineers is responsible for enforcing IAPMO’s Uniform Plumbing Code (UPC®) across the island, including plan reviews, plumbing inspections, and regulations around grease interceptors and water efficiency. As climate challenges mount, their work ensures that buildings in Honolulu are not only safe and up to code but also aligned with the island’s long-term sustainability goals.

Planning and Permitting

The team reviews commercial and large residential projects; essentially everything except for one- or two-family dwellings. The plumbing inspectors will inspect the latter for code compliance onsite.

“For the most part with sewer lateral connection to the city, to the cleanout, you can figure out where the piping is running,” Oku said, “and the contractors are supposed to call for inspection when it’s ready before they cover it up. It’s a lot more straight-forward, to make it faster; it’s code compliance by inspection.”

Oku said the department requires all permit plans to be submitted electronically. However, one- and two-family projects only need to show fixture locations on the base plans.

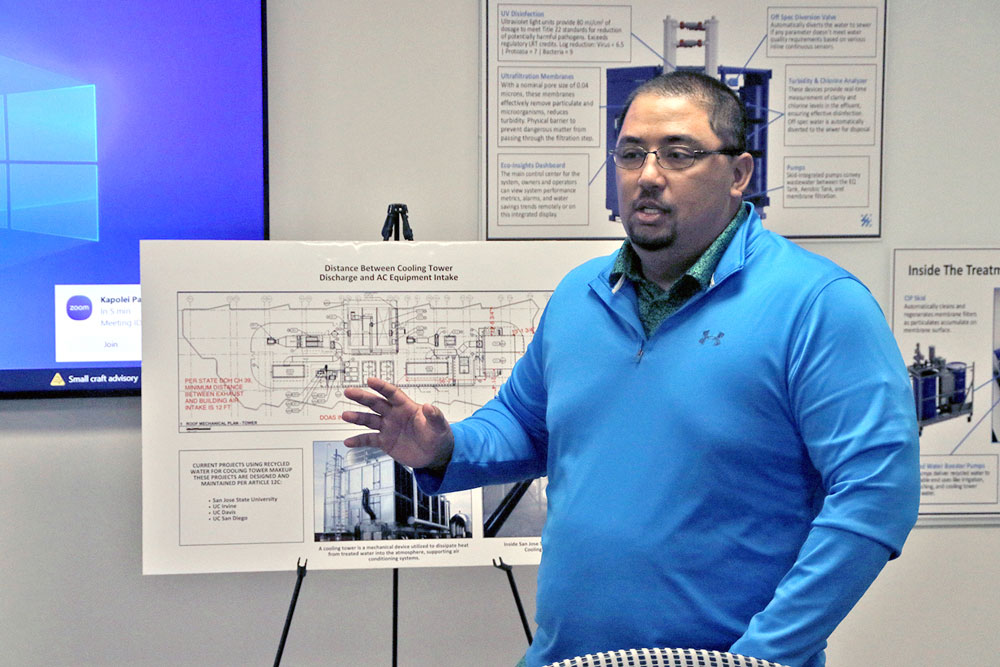

advocates and contractors. Center: Royce Rapozo, lead designer at Commercial Plumbing, explains the proposed greywater reuse systems to be

installed in two new condominium projects under construction in Honolulu. Right: Randy Hiraki, Commercial Plumbing president. | PHOTOS BY GEOFF BILAU

“For commercial, we require a plumbing plan and isometric piping diagrams,” he said.

The department’s 13 plumbing inspectors cover the entire island. Oku said the position requires them to at least be a journeyman plumber.

New hires go through a one-year probationary period before applying to become a regular inspector and then apply for senior positions as they become available.

Oku said many of their inspectors worked as journeymen until they reached the number of years required to collect union retirement before coming to work for the city. However, it’s a double-edged sword — while their experience is invaluable, they often do not work for the city for long before retiring. Due to this turnover, he said, almost half of their inspectors have been with the city for five years or fewer.

Chief Plumbing Inspector Keith Lee divides the coverage area geographically while also assigning the more complex areas to the senior inspectors.

“Every time we hire new inspectors or when somebody retires, he tries to redistribute the workload to be appropriate for the current crew that we have for inspection,” Oku said.

As for the types of projects they inspect, Oku said the city recently experienced an extensive build-out of high-rises, and though it has slowed down considerably some are still in the works.

“Housing is a big problem here,” he said. “Expensive housing.”

Although space is at a premium, Oku said new subdivisions for single families are under construction, including some with integrated townhouses. Meanwhile, owners of older homes are renovating them to make room for more people.

“In town, a lot of the older houses, they do renovations to allow for the children’s family to move in,” he said. “That’s a frequent

renovation.”

Right: Samuel Barrett Jr., assistant business manager, UA Local 675.

Third-Party Review

Faced with a surge of new construction projects and staffing shortages, Honolulu expanded the use of third-party plan reviews to keep permitting on track.

“Third-party review is hired by either the owner or developer,” Oku said. “Basically, it’s paid for outside. The arrangement is made as a private contract outside the city, and it has to be licensed professionals. They will do a review, a code compliance review, and submit their letter saying this is compliant.”

He said it began when about 25 high-rise projects were entering design or construction at the same time.

“We didn’t have staff for it,” he said. “The third-party review actually was there before, but they were not at the forefront. “The permit already includes a review. But if we couldn’t keep up because there were delays, then you could use third-party review.”

Even with third-party plan reviews, projects must still go through city inspections.

“For plumbing and electrical, they have to call our inspectors,” Oku said. “Building inspectors are tasked with periodic follow-ups because if there’s a project that does not show progress, they will terminate the permit.”

Originally limited to commercial projects, third-party reviews later expanded to residential as staffing shortages persisted.

“Right now, we have five vacant positions for mechanical review that we’ve been trying to fill for at least two years, maybe three years,” he said.

Oku noted that the city’s goal is to eventually reduce the reliance on third-party reviewers.

“If we have these positions filled, we can accommodate what third-party review is reviewing right now,” he said. “And being that its cost is included with the permit, the public will say, ‘Why not just get the regular review instead of paying somebody else thousands of dollars to do a review?’”

He emphasized that the third-party reviewers operate independently and are paid by the applicant, not the city.

“To me, it protects the city,” Oku said. “Right now, the city’s looking at doing a second-party review where we hire somebody to do a plan review for us because we are short staffed.”

While originally promoted as a way to speed up permitting, third-party reviews are sometimes taking longer than city reviews.

“Initially the thought process was, yeah, if you hire them, you can dictate, ‘I need it by two weeks.’ But they’re ending up taking longer than us now,” Oku said.

Right: Clayton Oku and Project Manager Trask Iosefa examine PEX piping at Park Ward Village.

PHOTOS BY GEOFF BILAU

Greywater Reuse

As Honolulu continues to grow, the city faces mounting pressure on its limited freshwater resources. Most of the region’s drinking water is drawn from underground aquifers, and with climate change intensifying drought risks, finding innovative ways to conserve water has become essential.

Greywater recycling — the treatment and reuse of lightly used water from showers, sinks, and laundry for non-potable purposes like toilet flushing and landscape irrigation — offers an attractive solution. By reducing the demand for freshwater, these systems help preserve aquifers and create more resilient communities.

A collaboration between the Albert C. Kobayashi, Inc. (ACK), Commercial Plumbing, Inc. — the state’s largest plumbing contractor — and Epic Cleantec is setting a precedent: two high-rise projects — Kuilei Place and Ālia — equipped with greywater reuse systems designed to meet the state’s highest water quality standards. The projects will utilize Epic Cleantec’s OneWater system.

“We’re just trying to create a better Hawaii because we are running out of water,” Commercial Plumbing President Randy Hiraki said during a meeting at the company’s headquarters in Honolulu that was also attended by city representatives and industry advocates.

For Kuilei Place — a 43-story luxury residential project — up to 30,000 gallons of greywater will be collected daily from showers, sinks and laundry in roughly one-third of the building, treated onsite, and reused for irrigation and toilet flushing. Projected to reduce the total water demand by 24%, the system will treat 8.5 million gallons per year and could save $133,000 in utility costs.

Ālia’s system will serve the entire 39-story building, with a capacity to use nearly 23,600 gallons of recycled greywater each day for landscape irrigation and cooling tower makeup. At full occupancy, Ālia is projected to reuse approximately 9.6 million gallons annually, saving about $93,000 per year for the next decade in utility fees.

The systems are designed to meet R1 water quality standards established by the Hawaii Department of Health. Each system includes filtration, UV disinfection, chlorine treatment, aeration chambers, and diverter valves that reroute water to the sewer in case of alarm. Real-time monitoring and data logging are required both during start up and after occupancy, with monthly reports submitted to the Department of Health.

Village. | PHOTO BY GEOFF BILAU

Collected wastewater is first stored in an equalization tank, which buffers flow variations and reduces the required capacity of downstream treatment systems. The raw wastewater then undergoes biological treatment to remove organic material, measured as Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD). Next, the water is filtered through membranes with a nominal pore size of 0.04 microns. Before being pumped back for reuse within the building, the water passes through multiple disinfection steps — ultraviolet (UV) light and chlorine — ensuring it is safe for non-potable applications.

Oku said as long as the Department of Health confirms that R1 water is coming out, the UPC applies to the rest of the system.

“The trickiest part would be any changes to that system would have to come to us for review,” Oku said. “We have a lot of projects that can go to a third party, but this would not be eligible for that for review. It will be new; it’s a process. We’re going to all learn through it together.”

Hiraki said ACK CEO Alana Kobayashi Pakkala wants to see if such systems can become more practical for their future projects.

“They are taking a lot of risk, taking money out of their profit,” he said. “But the developer is very proactive and she wants to go green, so they’re taking a risk. They hired us early to figure if this project could work, so we’re working together with the Department of Health and city and county of Honolulu, because she sits on a lot of boards.”

Hiraki said for its part, Commercial Plumbing is not charging for design fees and has been meeting with the city, Department of Health, and the Board of Water Supply.

He is optimistic the city will provide credits for connections and hookup fees as well and that Commercial Plumbing can receive financing help from the Ulupuono Initiative, a Hawaii-based impact investing firm that aims to improve the quality of life for island residents.

“Right now, we’re just out on a limb taking a chance,” he said. “We have a lot of cost out there, but I think the mayor [Rick Blangiardi] really wants to see it happen under his second term, that he’s going to help conserve water too for the future of Hawaii. That’s where this all got started.”

Hiraki said if these projects gain traction, the system could be utilized in another project for which they are negotiating that is larger than Kuilei Place.

“They’re looking at the capability of doing the same system if we can get it approved immediately,” he said. “And we’re running numbers for them, because I think they’re concerned about water usage too. The more proactive local developers understand that we’re running out of water.”

Implementing greywater reuse in a high-rise marks a significant departure from business as usual.

“To pipe a building like this, to work with the city and the Department of Health to get it approved, plumbing inspection is going to be a whole new ballgame, so we’re going to have to work together,” he said. “In order for Hawaii to take a step this big, we all have to step out of our normal comfort zone.”

Hiraki said the water shortage was exacerbated in November 2021 when petroleum leaked from the Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility into the drinking water well, contaminating the water for about 93,000 U.S. Navy water system users. Many were relocated until the drinking water system was restored in March 2022.

Hiraki said that was when the mayor stepped in and said he wants to participate and support the industry moving toward a reclaimed water system.

“That’s where the developer — Albert C. Kobayashi, Inc. — really stepped up,” he said. “They said they’d take a chance. I think a lot of credit’s got to go to them for taking that risk and working with the Department of Health and the city and county to get this approved. In several of the meetings we went to, the biggest concern for any developer right now on Oahu is water and sewer. That’s the issue.”

Kepa Resentes discusses the challenges and opportunities of the Park Ward Village project. | PHOTO BY GEOFF BILAU

Among their requirements with the State Department of Health is that during startup, there’s a period of a few months where they have to log data daily — sometimes even hourly — and submit the records to the Department of Health. Once the building is occupied and the system is turned over, they will continue recording that same data and submit it regularly to the state Department of Health.

“They review all of that information, and that includes any alarms or events that would trigger a system shutdown,” Hiraki said. “Even if the system shuts down for just an hour and then self-corrects, that still gets recorded and submitted. The Department of Health is the one responsible for overseeing and enforcing the water quality standards, and they’ll make sure we’re meeting the requirements they’ve established.”

Kika Bukoski, whose many governmental and labor roles included serving as a state representative and director of Government and Community affairs for UA Local 675, noted that the initiative had been a long time in the making and emphasized how much effort it had taken to reach this stage. He credited Genevieve “Genny” Salmonson — a longtime government advocate who passed away during the COVID-19 pandemic — for introducing him to the work. Salmonson had served on the National Blue Ribbon Commission for Onsite Water Reuse, which focused on advancing water reuse at a national level, with particular attention to the progress being made in San Francisco, a city that was far ahead in implementing on-site water reuse systems. Fifteen Fifty, a 40-story luxury apartment building that utilizes Epic’s system, is the first permitted and approved on-site greywater operation in the city’s history.

“She handed over her folders to me right before she passed away. At the time, I think she was with the state Office of Environmental Quality Control and was very active in this initiative,” he said. “She once told me it would take a lot of effort from all the stakeholders to really push this across the finish line. I’d like to think she’d be happy to see that it’s finally moving forward.”

Bukoski emphasized the importance of collaboration between the city, industry, and labor. He specifically recognized Oku and his team from the City and County of Honolulu for their long-standing commitment to upholding plumbing code integrity and supporting forward-thinking projects.

“Clayton and his group have always been staunch supporters of the plumbing code in Hawaii, and his desire to maintain the integrity of that code, I think, is why he brings up some of the concerns that he does. To have him sitting here supporting this project, for me, is pretty huge.”

The Park Ward Village

Following the insightful discussion at the Commercial Plumbing office, most of those in attendance headed about 15 minutes southeast to The Park Ward Village. Howard Hughes is the project developer, ACK is the general contractor, and Commercial Plumbing is handling the plumbing installation.

The building, which is adjacent to Victoria Ward Park, features a 41-story tower with studio, one-, two- and three-bedroom units, an amenities deck and a retail plaza.

Construction is expected to be completed early next year.

One aspect unique to building in Hawaii is the potential discovery of ancestral remains. During excavation at the Park Ward Village, crews encountered bones belonging to Native Hawaiians.

Commercial Plumbing project foreman Kela Abad said when remains are found, construction halts, and cultural monitors oversee the next steps. If possible, the bones are respectfully removed and relocated through a ceremonial process involving Hawaiian priests. In cases where removal is not feasible, remains are carefully preserved in place, with structures adjusted to accommodate them.

The tour group took an exterior elevator up 28 stories to the cast-iron floor, the foundation for the building’s drain, waste and vent system as well as storm drainage.

PHOTOS BY GEOFF BILAU

“This is where we start stacking up these cast-iron stacks and all of our waste stacks, just to catch all of our fixtures for the bathrooms, toilets, labs, kitchen sinks,” Project Manager Trask Iosefa said. He then pointed out some of the PEX piping installed in the slab, running up through the floor. “This is where we do our water supply, and we have a cold water riser that comes down and then we tie all that in when the studs are up.”

There was a noticeable blue and red covering on the PEX piping emerging from the slab.

“We call it ‘Smurfs’ but it’s just a protective sleeve and it’s for identification,” he said, noting that blue was for cold water and red was for hot. “The clear tubing inside is half-inch, and that is what feeds all the fixtures.”

He added that there is a copper manifold overhead, and then a copper line comes down and transitions to PEX piping.

This configuration allows each fixture to operate independently, improving water efficiency and maintenance access.

“It’s a home run to every fixture,” he said, “and every fixture his its own isolation valve, which is the angle valve.”

Iosefa said riser clamps throughout the building require acoustic isolation to prevent unwanted vibration and noise.

“It’s like an isolation pad,” he said, noting that every riser clamp must include one. Even the hangers, he added, are wrapped with insulation strip “for isolating for acoustical reasons.”

He added that this focus on sound control is one of the reasons cast iron is the preferred piping material in condominium construction. “Cast iron is actually the pipe of choice for condominiums because the sound attenuation is quiet, unlike PVC where you can hear it more.” While PVC would require additional insulation to meet sound requirements, cast iron’s natural density reduces noise on its own. That means smaller walls can be built around it, increasing usable square footage in each unit — “and that is what also drives costs,” he added.

He pointed out one of the risers on-site, noting that the cast iron waste lines are typically run above the water lines to maintain a clean vertical layout.

Walking through the unit, Iosefa pointed out a large open space that would eventually become a wet room. The bathroom features a double lavatory, water closet, shower and tub all integrated into a single wet zone.

“The tub will be all the way in — there’ll be a wall right here,” he said. “This whole thing is like one wet room, so the tub and shower pad together is one space. We’re going to see that when we go down to the eighth floor, which is the model unit. All of this is going to make sense when you see it, but to enter the tub you have to walk through the shower.”

Unlike typical configurations, the shower valve is installed on one wall while the showerhead is on the opposite side.

Waterproofing the space requires careful planning and sequencing.

“Usually, when it’s here, we put the tub up until the drywall comes out,” Abad said. “We put a waterproofing strip that’s included with the tub on the surround, and then we slap it in. And then GBI (Group Builders, Inc.) will build a wall, and then they’re going to have a subfloor that they float, the flooring guys. And then it’s all transition waterproof; they all waterproof it to this wall.”

“This is going to have a pan?” Oku asked, to which Abad replied: “They float it up with a mud bed, mud bed tile. So, when they make that mud bed, that transition, they bring it up to that wall that GBI will build and they just waterproof up to underneath the tub lip.”

The result?

“Seamless,” Abad said.

The group descended four flights of stairs to the 24th floor, where Iosefa identified a utility closet and how the cold-water main drops down and connects to the PEX manifold system. He showed where the water heater will be installed.

“This is our main supply for the water heater,” he said. “On the fixture end, we tie it in, set it here, and tie in all the hot and cold. Then we cycle it through and test it. We have an ice maker box here for the refrigerator.”

Resentes pointed out a washer stack and explained how it differs from the Sovent system.

“The washer stack is always its own plumbing,” he said. “It doesn’t tie into the toilets, lavs or anything because of the suds; they start washing with this heavy concentrated detergent. Sometimes things start coming up through your toilet and your shower.”

“The bottom floor pays the price,” Oku added.

Following an elevator ride to the 20th floor, Abad and Iosefa described the tub installation process while in a three-bedroom, three-bathroom unit. The tub includes stands with soundproofing feet and a waterproofing strip that snaps into place. Once the drain is connected and tested, the frame and tile finish will complete the installation.

“Typically, in past projects we did cast-iron tubs with skirts and then we’d have to put a bed of concrete, kind of set that to level it off and make it solid in the sitting on slab,” Iosefa said, “but for this one it’s a little different — it’s specced out differently.”

The final stop was in a finished unit on the ninth floor, which provided an up-close view of the amenities deck that includes a lap swimming pool, lounging area and pickleball and tennis courts, among other things.

The overall project manager, Kawika Nakoa of ACK, dropped in on the tour. He anticipated they would turn over the building in April 2026, and said owners would have a choice between a light or dark color scheme for cabinets and tiling.

He said each unit has its own water heater, but the mechanical system is centralized.

“In this building, we have a central condenser water system with heat pumps, not chillers, but the end product is still air conditioning,” he said.

PHOTOS BY GEOFF BILAU

Looking Ahead

Honolulu is taking practical steps to conserve water and support sustainable development, from requiring efficient plumbing fixtures in new construction to permitting greywater reuse in select high-rise projects. With growing demands on limited freshwater supplies, city agencies, developers, and industry professionals are working together to find solutions that meet both environmental and infrastructure needs.

As Oku said, “We’re going to all learn through it together.”

Mike Flenniken is a staff writer, Marketing and Communications, for IAPMO. Prior to joining IAPMO in 2010, Flenniken worked in public relations for a group of Southern California hospitals and as a journalist in writing and editing capacities for various Southern California daily newspapers.

Last modified: July 2, 2025