THE STAR CITY SHOWS OFF ITS FRIENDLY, EFFICIENT INSPECTION CREW AND SOME BIG CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS IN THE LATEST EDITION OF ‘PLUMBING A CITY’

Men’s Health magazine named Lincoln, Nebraska, the happiest city in America in 2020 thanks to high survey scores in mental and physical health, community, financial well-being, and environment, as well as 132 parks and 134 miles of trails. It doesn’t hurt that Cornhusker State residents are known for being so friendly that “Nebraska nice” became a slogan.

With relatively low crime and unemployment rates and affordable housing and rents, Lincoln continues to be one of the state’s fastest- growing cities. Originally founded as the village of Lancaster in 1856, the state’s second-largest city was renamed after the nation’s 16th president and became its capital in 1869.

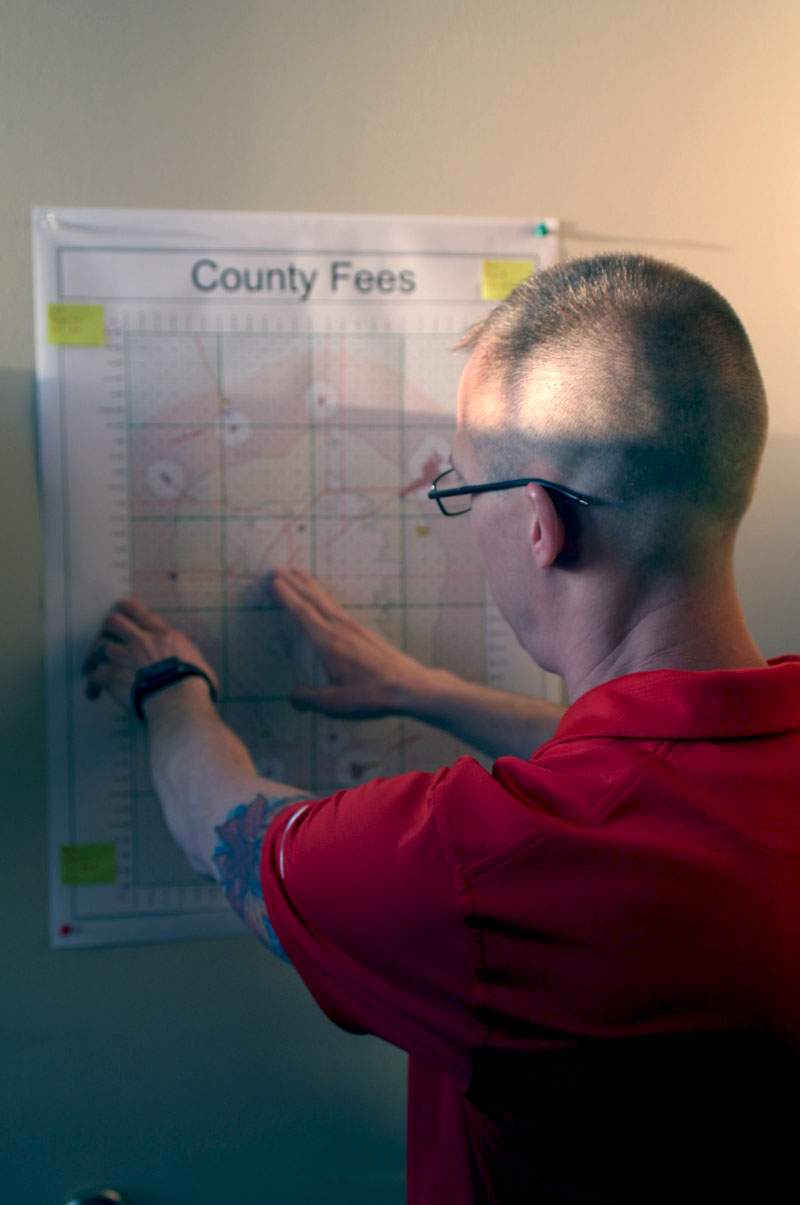

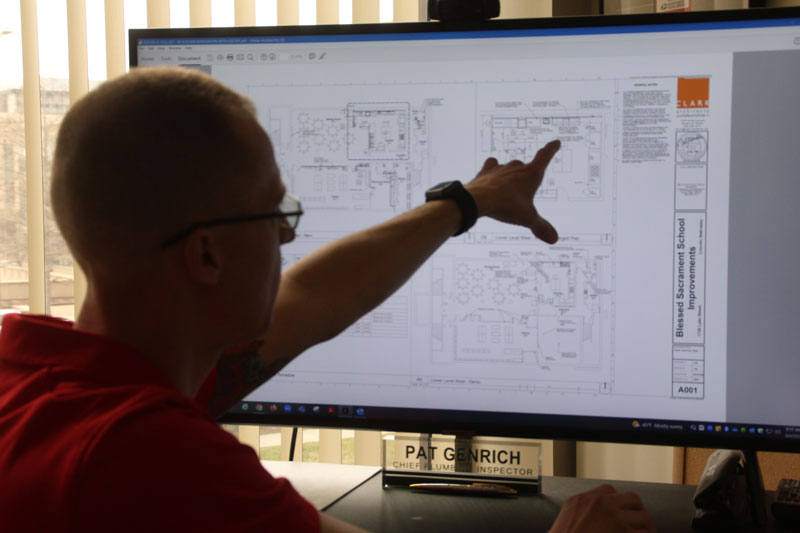

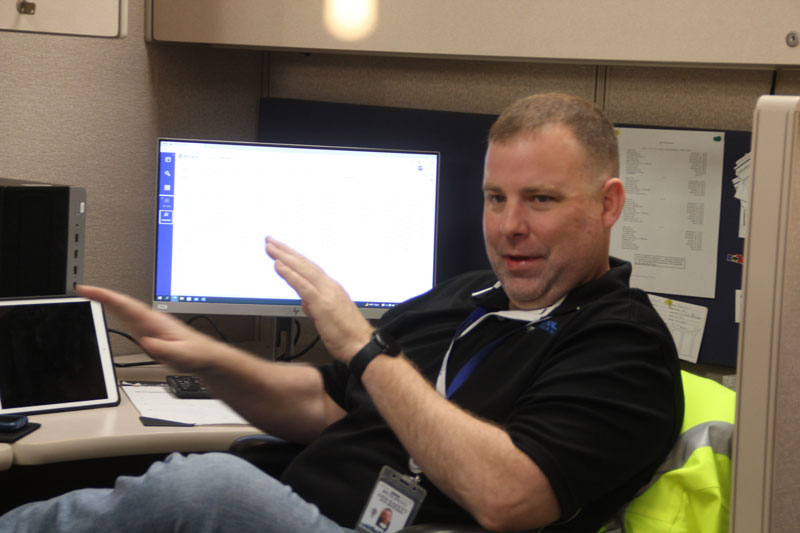

Lincoln’s Building & Safety Department is responsible for conducting plumbing, mechanical, electrical, and building inspections throughout the city. Chief Plumbing Inspector Patrick Genrich oversees a team of five inspectors, who cover not only Lincoln but all of Lancaster County, an area of approximately 772 square miles with nearly 325,000 residents. The Star City is governed by IAPMO’s Uniform Plumbing Code (UPC®), and Genrich and his inspectors make sure all the city’s commercial and residential buildings comply.

The inspectors conduct plumbing, fuel gas, medical gas and hydronics systems inspections; mechanical inspectors also look at hydronics projects, depending on how the contractor permits the work. Four of the inspectors — Jack Mogenson, Brian Morgan, Matt Schmidt and Karl Hesseltine — are assigned to one of the quadrants into which the city is divided, and the fifth inspector, David Howard, is considered a “floater” who helps out where needed.

“Dave will kind of take from the guys; they’ll give him what they feel would work best for him,” Genrich said during a visit by Official magazine to tour the department and some of the major projects it is inspecting. “He does a lot of our backlog stuff. On Thursday he’s going to an apartment complex where they had a lot of water heaters replaced and he’s going to do them all; I think he’s got 35 water heaters to look at.”

Genrich said during the summer they typically conduct between 100 and 120 inspections on a given day, and that range drops to between 60 and 80 during the winter. They perform both commercial and residential inspections.

“It’s a pretty good mix and it’s kind of moved a little bit over the years,” he said. “Downtown obviously is going to have a decent amount of commercial.”

Same-Day Inspections

Using a program called Citizen Access, contractors and homeowners can request a same-day inspection until 7:30 a.m., and they are for one-hour windows in the morning or afternoon.

“They can get onto Citizen Access 24 hours a day, seven days a week, pull permits and request inspections” Genrich said. “We don’t limit the number of inspections that we receive. The only limitation is that you’ve got to have them in by 7:30 the morning of,” adding that they will try to accommodate people who encountered issues submitting a request. Genrich said while the city encourages the submission of plans electronically, paper plans are still accepted.

“I’ve received plans on bar napkins,” he joked. “Primarily they’re going toward electronic, but they still take paper as opposed to when I started 10 years ago it was still paper primarily. I don’t know that any plans came in electronically.”

Lincoln’s

Development Services Center houses the city’s Building & Safety, Health, Planning, Public Works, and Urban Development departments.

Building & Safety Chief Plumbing Inspector Patrick Genrich discusses a map of the area covered by the inspectors.

Inspectors recently switched from laptop computers to iPads, though they still use the same program, Accela Mobile Office.

“I can put in an inspection and send it to their job list, and if they re-sync it’ll show up,” he said. “Same thing with the contractors.”

Through another program, VisualVault, inspectors and tradespeople submit their continuing education units (CEUs) — which Genrich reviews — apply for examinations and upgrade their licenses.

“This is one of those things I try and stay on top of because it can snowball,” he said.

“PHCC does a trade show, and then in that same month 811 does a Diggers’ Safety Expo and there are hundreds of CEU forms that come in. I will walk in here on the 6th or even sometimes Friday afternoon and I will see 50, 60, 70 CEU forms.”

From Inspector to Chief

Genrich succeeded former IAPMO board member Rex Crawford as chief plumbing inspector in January 2021 after nine years as a plumbing inspector for the city. Crawford took over for former IAPMO President Bob Siemsen — whose last hire was Genrich — in 2013.

“I worked with those guys,” Genrich said of the inspectors he now oversees. “They’ve been extremely good to me as far as me stepping into this role. There hasn’t been that pushback as there could have been. So that has also been extremely helpful. That’s made the transition smoother.”

Developing a day-to-day routine and not letting work build up have been key to his success so far, and he said the inspectors are good at keeping him informed about what is happening in the field while still being able to handle most issues themselves.

“And they talk to each other to say, ‘Here’s what I’m looking at; what do you think about this?’ he said. “Because our code is printed in black on white paper, but it is not always black and white.

“You get into some of these older buildings, you get into some of these situations where there’s a lot of gray and you’ve got to make a judgment call. Judgment calls are tough because they’re not 100 percent right, but they’re not 100 percent wrong. But if we’re all being consistent in that situation, in that moment, everybody can pretty much agree that it makes it go better.”

In addition to Crawford and Siemsen retiring, the city lost longtime inspectors Bill Fleischman and Jim Skinner to retirement, each of whom had more than 25 years’ experience. Genrich said he talks to Crawford daily and Fleischman still does part-time work, so they can still benefit from their decades of experience.

“The open communication has been really helpful all the way around, I think with us relating it to contractors with the previous coworkers helping us along the way. We did lose a lot of that experience, but it’s not necessarily gone for good.”

Chief Plumbing Inspector Patrick Genrich oversees a team of five inspectors who cover approximately 772 square miles and nearly 325,000 residents.

Sewer cards waiting to be scanned into computer, which keep track of all sewer installations.

Genrich said the department’s biggest challenge is doing a high-quality job in a timely manner each day. For inspectors, every day is different because they are dictated by the requests they receive. Once those come in, each inspector must figure out the best plan of attack for that day. Genrich will often cover for one of the inspectors if they are out, which adds to his workload.

“Plans don’t stop coming in, phone calls don’t stop coming in, emails don’t stop coming,” he said. “So just juggling all that and then being able to turn it off at night is probably the biggest challenge.”

Black Hills Energy, which provides gas service, is in the third year of a decade-long project to relocate an estimated 12,000 meters to outside of the home to make them more accessible for reading and servicing.

“Jack had a lot of those last year and Dave was able to help him, and Karl’s getting some of those now because they’re straddling the line of both areas,” Genrich said.

The city also offers single-fixture permits for such projects as food waste disposers, dishwashers, kitchen sinks and shower replacements, which are less expensive but must accompany a request for a standard permit.

“If we’re there for a water heater or water conditioner or different remodel, we’ll look at those when we’re there,” he said. “We did almost 12,000 permits last year, but that doesn’t factor in the single-fixture permits. The year before that we had almost 13,000 permits.”

The Inspection Team

During a group interview with the inspectors, Hesseltine agreed that scheduling was the most difficult part.

“Trying to stay on top of your day would probably be one of the biggest challenges, just because of the numbers and such,” he said. Hesseltine was a plumber for 27 years before becoming an inspector, and he actually worked with Howard, another of the inspectors, at the same plumbing company.

“It’s a big change to go from being the guy out there doing the work to being the guy who’s looking at the work,” he said. “You learn certain ways while you were doing it and then you get into this position and people do things differently. It may be different than how you do it, but it still meets code, so you have to sort through a lot of that kind of stuff.”

With only a year as an inspector Howard is the newest of the group, but he had to learn quickly because as the floater, he travels throughout the coverage area.

“I’ll have to be out in the county in Jack’s area, and then I’ll have to go down to Brian’s area,” Howard said. “It’s a lot of hustling, but I don’t really have any problems. It’s a new experience and I kind of enjoy it, helping keep people in line.”

Schmidt said for him, the biggest challenge each day is making sure the inspections are done properly because of there are so many different types.

“We get the big variety of a 10-story building to looking at a water heater,” he said. “Making sure everything is done correctly in the timeframe; some days it gets really busy.”

Morgan agreed with Hesseltine about scheduling challenges, explaining that it isn’t uncommon to be tasked with five inspections before 10 a.m. He said it can also be a challenge dealing with multiple contractors for a job as well as multiple plumbers, such as one for hydronics and another for the rest of the plumbing.

“A lot of times if they’re not talking, it’s up to us to keep everything in line,” he said. “Things can get lost in translation pretty easily if you’re not on top of it.”

As with many cities, people are increasingly seeking to live downtown in Lincoln, and the historic Haymarket District is a well-known destination.

“One trend that I’ve definitely noticed is a lot of the restoration of all the older buildings downtown turning into condos, and downtown living has become a big deal in Lincoln the last few years,” Mogenson said. “So, the whole Haymarket renovation, it’s turned into a really popular thing. Some of these old historic buildings are now new construction, and downtown has really picked up the pace and it’s been awesome. The Haymarket’s a great area.”

The Tour

Genrich led Official on a tour of several prominent projects in Lincoln that are going through the inspection process, including a cancer center, a new high school, and a student apartment complex.

April Sampson Cancer Center

The first stop was at the April Sampson Cancer Center, a 140,000-square-foot facility in south Lincoln that will offer advanced technology and treatment in a healing, comfortable environment. John Sampson, president of Sampson Construction, his daughter, Cori Vokoun, and her husband, Dan Vokoun, both vice presidents at Sampson Construction, donated nearly 29 acres of land for the cancer center, which will be part of Bryan Health.

Sampson Construction is building the cancer center, and Grunwald is the mechanical contractor. The entire project was building information modeling (BIM) coordinated, so a three-dimensional model shows the different trades where their equipment should be installed. In the office trailer, Grunwald project manager Nick Huelle gave a quick virtual tour of the project.

“So now we’re up on the roof looking down into level one,” he said. “You can drop through the floor, down into the lower level and underground. Here’s the mechanical room — boilers, pumps; everything’s coordinated down there.” Outside of the cancer center, Genrich pointed to a wing on the second level in which plumbers would install hangers and 3D mapping would identify where everything would be installed.

“It looks like modern art because they’re not allowed to drill into any of the concrete or anything like that,” he said. “So, they’ve had to span with Unistrut and all that stuff to get all thread, auto grips and clevis hangers, it looks really, really cool.”

The center will use a combined storm drainage system in which the primary and overflow roof drains will enter the same vertical riser before going into the ground, requiring the pipe to be larger than usual.

“When you combine the systems, you’ve got to take the rainfall rate and double it,” he said. “That way the pipe will handle it. Here currently our rainfall rate is 6 inches for the first hour, which is quite a bit. So, when they do a system like this, they’ve got to increase it to handle 12 inches for the first hour. That’s why the pipe sizes increase so much.”

Grunwald Mechanical General Foreman Trevor Dohrman said they had to use Unistrut every- where for supplemental steel because they were not allowed to hang anything from the actual concrete. They used Propress fittings for the domestic water system and Victaulic pipe joints for the 2 ½-inch and larger steel pipe.

He said thanks to the BIM technology they are able to get in and do their work without having to coordinate with anyone else. “We know we’re bottom of pipes,” he said. “The HVAC guys know they’re bottom of duct and all that. And everybody can throw hangers in and then come back in when these walls go up and finish piping and doing all that.”

Project superintendent Corey Tuck with Sampson Construction said using BIM can help clear up any misunderstandings.

“I’ve done it both ways, but as far as fire- proofing and getting ahead of the game, it’s a lot more efficient,” he said. “And then there’s no misunderstanding when you get to the point where framing’s up and pipes are run. If you missed your elevation, that’s on you. It eliminates a lot of rework.”

Dorhman agreed.

“The saying is ‘BIM is bible,’ so if it shows that in the BIM, that is what it is,” he said. “There’s really no argument over it. It does help the coordination side; it makes it kind of nice because if somebody’s in the wrong spot, you can pull it right up and find out who’s got the right of way, I guess, on it.”

Welders at the April Sampson site.

The tour continued down a long hallway where infusion bays will look out over a lake and extensive landscaping.

“This will all be glass; this whole building is pretty much glass too,” Dohrman said. “They’ll be getting their chemo in these infusion bays being able to look out in a peaceful setting.”Dohrman was asked if he had encountered any difficulties on the project.

“They consider this a design build, so that’s kind of an interesting new thing with the architect, allowing us as professionals to kind of make our opinions on it, and then we have to submit RFIs into that and get the OK on it,” he said. “A little different than having just the answers out there, but it’s kind of been interesting to work with. I know that’s kind of a newer thing that they’ve been going to more of.”

In the main mechanical room, which contains three boilers, Genrich pointed to hangers that were installed for future piping.

“They’ve got their air separator, and they’re tied in back there to all the boilers,” he said. “This will run all the heat and everything, and there’s hydronics throughout the building, especially with all the glass.” Dohrman said the room’s entire layout was drawn three dimensionally down to where the boilers sit.

“Our shop up in Omaha has the capabilities to prefab all this, so they built these headers, all this pipe,” he said, “and the rest of the big pipe that comes in here, they were able to build that up in Omaha, send it down to me. We start hanging, we come in with boilers and we can start making the connections. It really speeds up the process being able to do that prefab up in Omaha, and then we kind of just piece it together like a puzzle basically when it comes down here.”

All of the domestic water supply originates in the mechanical room, which includes two water heaters, Dohrman said, and the medical oxygen bottles will be stored in an adjacent room. “The heart and soul of it’s all kind of down in the mechanical room; it all comes back into here,” he said.

The imaging area includes an MRI machine and CT scanners, as well as three Linac linear accelerators, which aim radiation at cancerous tumors.

“The bases on the Linacs, there’s a tolerance of 0.03% of them being out of whack,” Sampson Construction superintendent Austin Campbell said. “So, they have a guy who comes in, he’s got a very special level that he sets on these and they have to be dang near perfect. So that’s why we don’t allow anybody to walk on them, step on them until we get the concrete poured back, and even then we barricade them just so guys aren’t walking across them.”

“Up there you can see where all the different systems come in,” Genrich said. “Med gas, water, everything, and you’re going to have a heat sink here.”

The tour ended on the roof, which has air handling units that are hidden by shrouds so they won’t be visible from the road.

“The day we set these it was cold; it was like 5 degrees outside,” Dohrman said. “It was miserably cold. That was one crane day. We set all five. And then on the other side, there’s three more air handlers, and then we did that another day. And then about two weeks later, we came and set these two. Really the only thing that we have connecting to these is gas.

Russell hooked their ducts from underneath there. And then over here we have makeup air units. These step-ups here are for all those condenser units that’ll sit up on the roof.”

For Buck, the Sampson superintendent, the opportunity to be involved with such a project has special meaning, as he like most people, has been affected by cancer.

“This project’s been touching to me just because my grandpa’s had cancer, my dad’s had cancer,” he said. “It was a kind of an eye-opening experience and it’s going to be gratifying for all of us to be able to contribute to all the individuals who are battling cancer.”

Standing Bear High School

The next stop was about 3 miles east of the cancer center, at a new high school named after Chief Standing Bear, whose Ponca tribe lived on the west bank of the Missouri River and along the present-day Niobrara River and Ponca Creek in northeast Nebraska.

Scheduled to open to grades nine and 10 in August, the school was designed to ultimately accommodate 1,000 students.

“We’ll start in the big mechanical room,” Foreman Aaron Lyons of HEP Inc. said. “This is kind of the heart of the heating and air part; geothermal heat pump loop. We’ve got two 14-inch pipes that go out to a geothermal well out underneath the parking lot. And then the pumps circulate all that water through all the heat pumps throughout the building.”

Genrich pointed out that unlike the cancer center, where everything was computer modeled, much of the work for the high school was field designed.

“Two different ways of doing it,” he said. “Communicating, coordinating with trades on site, having the computer generate everything and map it out for you. Which one took more or less time? It’d be hard to tell you. But at the end of the day, both site still have quality work.”

Lyons said Standing Bear had an identical floor plan to that of Northwest High School in Lincoln, on which he worked for two years.

“The challenges, for the most part, are corridors because they try to condense all the piping and all the duct work in the corridors, and you run out of structure really fast,” he said.

Lyons said thanks to sponsorship from a local bank, Standing Bear High School will offer a program in which students perform the role of teller, learning to count money and interact with customers. He said similar programs are starting in Lincoln elementary schools as well.

The administrative offices will have a VRF system so that each one will have its own air conditioner.

“These are the VRF heat pumps,” Lyons said. “The heat pump water cools or heats the refrigeration water. This is the first time in any job that I’ve ever been on where we’re combining the refrigeration side of it with the heat pump side of it.”

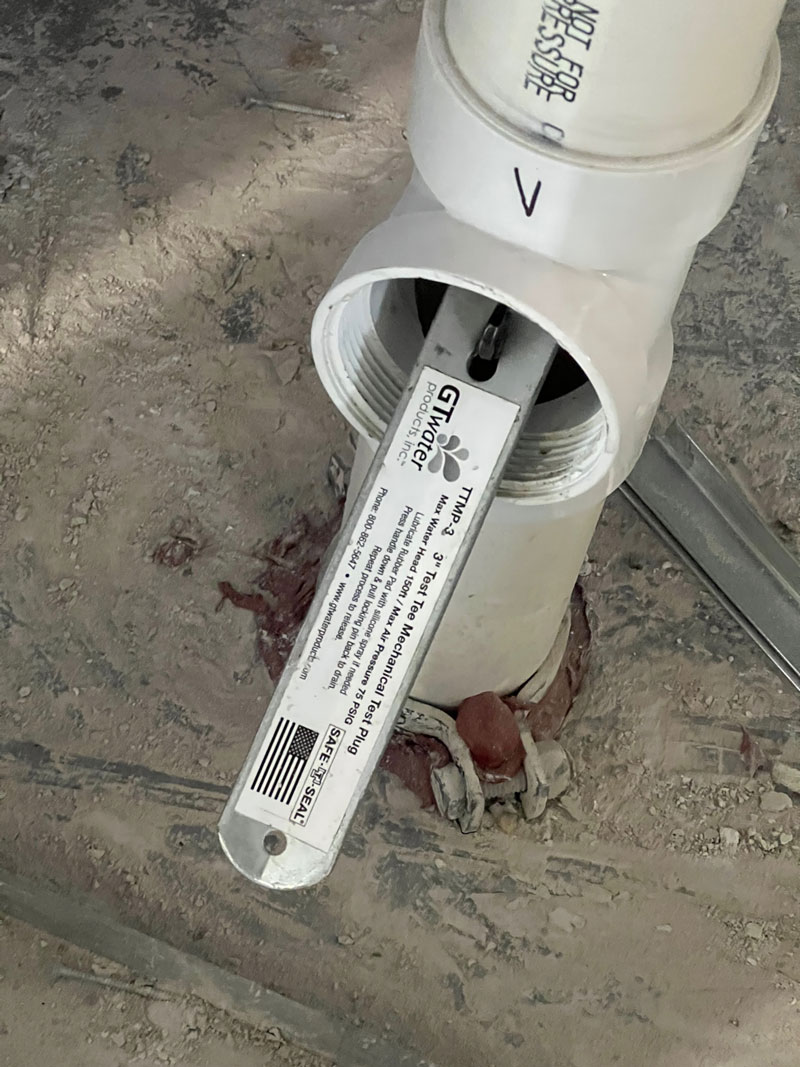

Genrich said inspectors require hydrostatic tests that involve filling the system with water at a pressure of 100 psi and then walking it to check it for leaks.

“Sometimes we find them, sometimes we don’t, because a lot of times the good ones will do the hydrostatic test before we’re there and then check for themselves,” Genrich said. “But it is part of the inspection process to ensure that each system doesn’t have any leaks.”

Lyons said they hadn’t built much classroom space yet, instead focusing on such core structures as the kitchen, cafeteria, gymnasiums and the pool, but will add classrooms as it expands.

“There are futures for all the domestic, the sewer and the heat pumps,” he said. “These pipes right here are for the future if they ever expand that way so they don’t have to cut into the system.”

“When they design these, they design a hub,” Genrich added, “and then the fingers that come off them are all the future branches.”

Lyons, whose career has spanned 25 years, was asked why he went into the trades as opposed to taking the more traditional path of going to college.

“The fact that I had to feed my kids,” he said. “I was in school spending money. I actually went to Southeast Community College in Milford for the HVAC program, but couldn’t afford to be going to school and feeding the kids. So, they had an ad in the paper, I called them, was hired the next day and have been here for 25 years. Worked my way up.”

The school will also have a robotics lab in which the students will be able to design such things as fighting robots on their computers and then build them. There will be numerous breakout spaces for small-group work that can be sectioned off or left as a large open area.

The tour continued to other areas of study that, though recognizable to people who were in high school several decades ago, have been modernized.

“This is the industrial arts,” Lyons said, “so wood shop; they’ll have a whole dust collection system, there’ll be benches set up throughout here with workstations, power tools. They have a room back in the corner, it’s like a finishing room where they can do staining and all that. They have a ventilation hood in there.”

The school will also teach home economics, now known as family and consumer sciences. Each lab station in the classroom will include a gas stove, microwave and sink.

“These are all gas,” Lyons said. “That’s what these access doors are for here; all the gas piping to these islands goes underground.

Restroom at Standing Bear.

And on the other side of that wall, we’ve got a manifold where the gas piping comes from overhead and then feeds everything underground. And then it’s all sleeved inside a PVC pipe and vented back out the roof separately.”

The school will have a series of small rooms called innovation labs that focus on specific careers. Northwest High School, for example, received grant money from Bryan Hospital and they offer a nursing program, so its innovation labs have hospital beds and dummy patients. Standing Bear received grant money from the University of Nebraska’s College of Business, so it will be geared toward business and accounting.

“The public schools in Lincoln are kind of going that niche route where if you want to be a business major, this is probably the high school you want to be in,” Lyons said. “North Star High School got money from Duncan Aviation and they’re building a big aviation maintenance wing.”

Lyons said the biggest change he has seen in his 25 years in plumbing has been the type of material being used — more plastic, less metal.

“The means and methods have pretty much stayed the same. I was the last journeyman’s test on the old Lincoln code,” he said. “But we were already implementing the IAPMO code in the field, so I was kind of in that class where I’m learning one thing, but I’m not doing what I’m learning to get my license in the field.” Lincoln adopted the 2000 edition of IAPMO’s Uniform Plumbing Code (UPC®) in 2004 and has continued to adopt subsequent edition.

How would Lyons compare the two?

“Night and day,” he said. “There’s a lot of differences between the way we do things now as far as sizing sewer pipes, requirements for venting, sizing a water pipe, all that stuff. We just went off what the engineers did; we never had to know how to do it. Now, I’m teaching all of my apprentices and future journeymen, ‘this is the way you have to do it.’ ”

“It’s good to know the why, not because Aaron told me to do it, but I’m doing it because I know the codes,” Genrich said.

“The theory as to why you’re doing it,” Lyons said.

“That way when Aaron’s not standing there with you, you can go and do it yourself,” Genrich said.

The tour continued through the auditorium and past the competition gym (there is also a practice gym), which may be seen through windows in the cafeteria.

Lyons pointed out the window toward a brick building on the school grounds.

“That’s where the geothermal well field comes up out of the ground and it’s a big header,” he said. “And then the far one is the water service with the water meter and backflow preventers.”

Genrich said the private system begins after that building, and it is where the city’s jurisdiction begins as opposed to Lincoln Water Systems.

“We did all the inspections on everything from there this way, and there’s a manhole not too far from there; that’s where the sanitary sewer started,” he said. “We did all the inspections on that as well. It did not look like this when we were out here doing inspections. This was a gigantic hill.”

In the kitchen — which he said was probably one of the largest commercial kitchens they had done in a long time — Lyons said the main trunk line is cast iron out to the grease trap, and there is a secondary sewer for such things as hand sinks.

“There are two sewers that run through this kitchen,” he said. “One goes to the grease trap, one doesn’t. And they run opposite directions.”

Inside another mechanical room, Lyons said, “One of the interesting things they’ve got going on is there are two heat exchangers. They use the residual heat from the heating water to preheat the water going into the water heaters, so they don’t have to work as hard.”

Just outside the science labs, there is a roof with green space that will be filled with plants and a path consisting of pavers.

“There’ll be a reduced pressure principal backflow preventer, in one of the mechanical rooms down below,” he said. “But where that pipe comes out of the wall, there’ll be a big cistern that sits on the roof; that’ll pipe into it and it’ll collect rainwater in the summer and then they can use that to water the plants. If that’s dry, then they’ll have this option to be able to water,” pointing to a stub that can be used for irrigation.

As the tour through the school concluded, Lyons said, “If you want to peek, they’ve got the swimming pool full. They’re flood testing it. It has to sit for two weeks to see if the water goes down.”

Atmosphere

The final stop was in the center of the city at an apartment building that will house students at the nearby University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Located at the former site of the Lincoln Journal Star newspaper office, the Atmosphere consists of a six-story wood-frame building on the northern side and a 13-story structure that was pre-engineered using an Eisen building system on the southern side. A courtyard with a turf area, movie screen, barbecue grills and a hot tub is in the middle. There will be more than 700 four-person rooms between the two buildings.

Eric Stone of Green’s Furnace & Plumbing Co., the plumbing and mechanical contractor, led the tour, which quickly came upon two plumbers, Grant Davis and Jon Thompson, who were running water mains for the building.

“We’re doing ProPress fitting; basically push-together gaskets,” Davis said. “We kind of got away from brazing. It’s way quicker. A little bit harder to get fittings, but they work way better.”

Davis said he prefers using ProPress fittings, as he had not yet encountered one that leaks, and the process was user-friendly.

“The gun’s heavy, but it’s 10 times faster than any brazing you’d ever do,” he said. “It’s more efficient, too. And the pipe can be wet when you seal it.”

Genrich said the project is in several different phases.

“These buildings obviously have all had their rough-ins inspected,” he said. “They’re dry-walling, and then before long we’ll be coming back to inspect the finish after the cabinets go in, the flooring, everything like that.”

Through large windows in a second-floor corner unit, Genrich pointed to the street below.

“Straight down there is the football stadium,” he said. “This whole corner will be flooded with red, all day long, on game day.”

Tim Knickerbocker, jobsite superintendent for Hausmann Construction, said for the side with the Eisen system, they would put up the trusses, pour concrete and stack the next one on top of it.

“We were averaging about a floor every week, week and a half,” he said. Stone was asked what the most difficult part about the job site had been.

“In this country we’re experiencing a manpower shortage and it’s no different on this job site,” he said. “When we first started and we were hit with the schedule, you don’t know what the schedule is; it’s going to be prebid. You don’t find out until that first construction meeting. And then we found out we’re a little short staffed. Picking up staff and getting the job staffed is probably the biggest hurdle.”

As for the best part?

“The best part is always the camaraderie with all the other guys.”

Genrich pointed out that because time was particularly of the essence for this project — they want to have it ready for the start of the next school year — they are using ProPress, PVC and PEX as much as possible.

“The job is tailored material wise to be quick, so anything that we can use to shorten the completion time of a job phase, we’ll go ahead and do it,” Stone said.

Another challenge is a lack of space for workers to stage their equipment and materials because buildings in the area are so close together.

“This is a perfect example of no room,” Knickerbocker said looking down from the ninth floor. “You can see where the barriers are. Technically that’s sitting on the bank parking lot, so that’s kind of our footprint around the whole building.”

Genrich said because the building is more than 10 stories tall and has such a large plumbing system, the code requires yoke vents be installed.

“When you get up so high in a building, you have to create reliefs in the vents, and that’s what these are; they’re just an extension off of the drain stack, and that goes up and eventually ties back into the pipe here, creating a relief of air,” Stone said. “Just so you don’t have a big column of water coming down that pipe, you’ll need a relief of air to keep the vent usable. We did that three times in this building; this is the last of the three sets going up.”

On the 10th floor, Stone pointed out one of multiple temporary things he said they must put in a building like this one.

“That’s a temporary gas riser used for temporary heat,” he said. “In some situations, they have to heat the building, like for drywall compound, head testing with water, we have to be above 40 degrees so that’s how they bring in temporary heat.”

Genrich pointed to where everything will be attached so they could perform their head test to check for leaks.

“We’ll walk the floor below and then come up here and check to make sure the pipes are still full,” he said. “We walk them to make sure nothing’s leaking.”

The tour ended in the lowest level, which will also be utilized as a parking garage. “Most of the drainage ends up down here,” Stone said. “Everything that we saw tied into the walls are the same sets of pipes coming down and tying into this main branch line.”

Genrich said when the plans first came through for the drain waste and vent, he had to reject them because the stacks were undersized.

“Luckily these guys actually caught it, because the plans they bid off of were the pre-approved ones,” he said, “so they actually caught it on their end, too. That comes with skill and training, doing this, and knowing that what we get the first time might not actually be what is the correct set. The cost difference between 8-inch and 6-inch, or 8-inch and 4 inches, it’s pretty significant, especially when you’re ordering 11 miles’ worth of PVC at a time.”

Team Effort

The tour of projects in Lincoln continuously highlighted the collaborative relationship the inspectors have with contractors and trades workers, and Genrich pointed to that as one of the department’s strengths.

“We try and work with people as best we can,” he said. “We are the code official; we are the administrative authority. But we still have to work with these guys at the end of the day. That doesn’t mean that we let them get by with things that aren’t compliant, but we don’t have to come in here and throw a big hammer around and say, ‘Because I said so.’ We’ve got to be able to work with them and educate at the same time. We’ve got to have a plausible reason as to why, and then explain to them why, and I think we try and do our best at that.

Consistency is something that I’ve always tried to do; just be consistent from one job to the next. That way people know what to expect, and they know what is expected of them. I think that’s something that we’ ve done really well, being consistent, and just working with our tradesmen and our citizens. Because at the end of the day, we are public servants. We work for the city.”

Mike Flenniken is a staff writer, Marketing and Communications, for IAPMO. Prior to joining IAPMO in 2010, Flenniken worked in public relations for a group of Southern California hospitals and as a journalist in writing and editing capacities for various Southern California daily newspapers.

Last modified: May 8, 2024