Over the past century, plumbing regulation has evolved from fragmented local rules into a unified, consensus driven system that now safeguards public health for nearly half of the world’s population. At the center of that transformation stands the Uniform Plumbing Code (UPC®), developed and maintained by IAPMO. Its history is inseparable from the modernization of sanitation, the professionalization of plumbing, and the global push for safe, efficient water infrastructure.

Early Foundations (Pre-1945)

Long before the first UPC was published, U.S. cities began issuing their own plumbing regulations in response to severe public health challenges. For example, New York City’s 1881 Plumbing Law established the first plumbing code in the United States that standardized sewer connections and required registered plumbers on approved jobs.

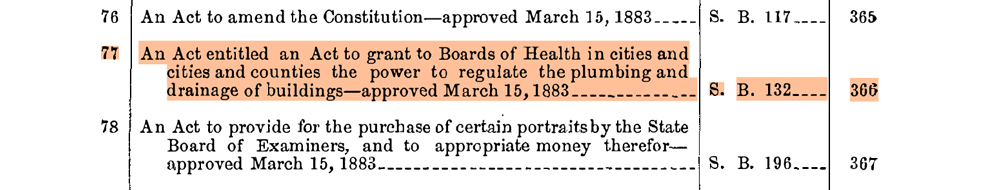

A couple of years later in 1883, California Senate Bill No. 132 was enacted, giving cities and counties the power to regulate the plumbing and drainage of buildings.

Other states followed similar regulations such as Pennsylvania authorizing the board of health to regulate house drainage in 1895. These early regulations included health and safety provisions that standardized the way plumbing is done. It required traps for all sinks, basins, and water closets, including vents for all traps to prevent sewer gases from entering the buildings. These regulations laid the groundwork for a unified model that could be adopted across jurisdictions.

At the same time, national and local plumbing organizations emerged, recognizing the need for standardized sanitary practices.

The Birth of the Uniform Plumbing Code (1945)

The UPC, as we know it today, was first formally published in 1945. It originated through the work of Los Angeles plumbing inspectors who formed the organization that would become IAPMO, officially founded in 1926. Initially adopted only in California, the UPC quickly gained traction as jurisdictions sought dependable, model plumbing standards.

A meeting of the National Plumbing Code Committee in Washington, D.C., with founding members of the Western Plumbing Officials Association (WPOA), the original name of IAPMO.

This first edition marked a turning point — shifting from scattered local practices to a consistent, consensus based code. Plumbers throughout California looked to the UPC for guidance for safe and proper plumbing installations.

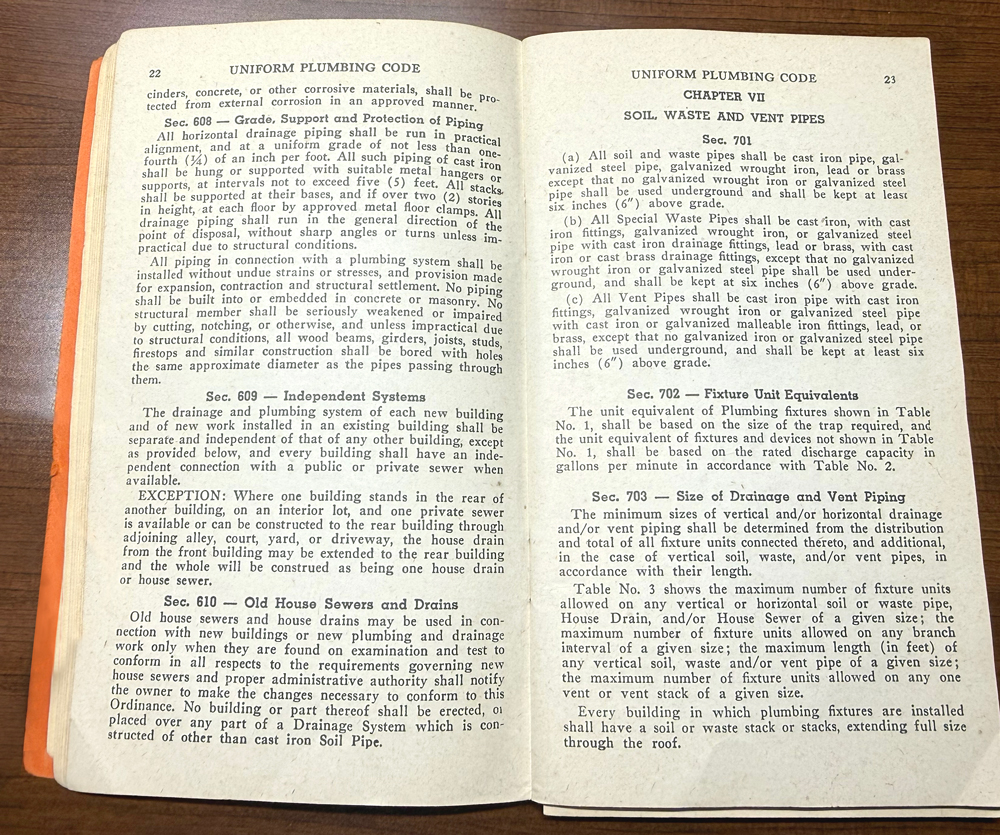

This early version of the UPC included much needed provisions for the Responsibility for Plumbers; Soil, Waste and Vents; House Drains; Special Waste; Plumbing Fixtures; and Private Sewage Disposal Systems.

The original 1945 edition consisted of just 71 pages with only three sections per page — a compact booklet that could easily fit in one’s back pocket. It was common for plumbers to be carrying a copy of the 1945 UPC in the field.

Sections on house drains, plumbing fixtures and private sewage disposal systems from the 1945 UPC.

Mid Century Expansion and Modernization (1945–2000)

Several factors fueled UPC expansion during the mid-20th century:

- Public Health Needs: Post WWII construction booms and improved understanding of sanitation drove demand for reliable plumbing standards.

- Health and Safety Provisions: The UPC became known for balancing safety and innovation, guiding water distribution, drainage, venting, sanitation, and specialized systems.

- Consensus Development: The consensus development process ensured input from inspectors, engineers, labor, manufacturers, and consumers, resulting in widely trusted code provisions.

21st Century Acceleration and Global Reach (2000–Present)

In the 2000s, the UPC surged beyond North America as global regions sought dependable codes that aligned with modern health, sustainability, and engineering practices. The code’s three year update cycle ensures continuous integration of new technologies and best practices:

- Health and Safety Provisions: The UPC became known for balancing safety and innovation, guiding water distribution, drainage, venting, sanitation, and specialized systems.

- Consensus Development: The consensus development process ensured input from inspectors, engineers, labor, manufacturers, and consumers, resulting in widely trusted code provisions.

- Public Health Needs: Post WWII construction booms and improved understanding of sanitation drove demand for reliable plumbing standards.

- Accredited Development Process: The publication of the 2003 edition was a significant milestone because it was the first time in the history of the United States a plumbing code was developed through a consensus process accredited by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI).

- Growing Influence: By the late 20th century, UPC adoption was common across the western United States and internationally. Today, UPC-based codes influence plumbing practices in regions such as India, the Philippines, Rwanda, Indonesia, Kuwait, Jordan, United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia, demonstrating its global applicability.

- Innovation and Research: The UPC has incorporated cutting edge provisions that have vastly enhanced and modernized the UPC since 1945. Provisions like water efficiency fixtures, Legionella mitigation, onsite water reuse, and pipe sizing methodology — most notably the Water Demand Calculator, the first statistically based water pipe sizing method since the 1940s. To address leak detection, devices covered by the IAPMO/ANSI/CAN Z1349 were added. These leak detection devices include features like automatic shut-off or electronic alarm notification when a leak is detected in a plumbing system where such notifications can be sent via a smart phone. Drinking water treatment units such as Alkaline Water Treatment devices are addressed by IAPMO IGC 322 and scale reduction devices manufactured to IAPMO/ANSI Z601. Alternate water sources for nonpotable applications have been included to address greywater reuse and minimum water quality requirements such as IAPMO IGC 324. Rainwater catchment systems were also added to address the use of rainwater for non-potable and potable water applications. Non-sewered sanitation systems in accordance with ANSI/CAN/IAPMO/ISO 30500 address applications where there is a lack of a sanitation system. To address the growing trend of indoor horticulture facilities, provisions for water supply, storage tanks, fertigation and irrigation equipment provisions have been added for indoor horticulture facilities. And many more!

- Broader Scope: The UPC now coexists with IAPMO’s wider catalog of codes — for mechanical systems (Uniform Mechanical Code); solar energy, hydronics and geothermal; and water efficiency sanitation standard — reflecting a comprehensive approach to building safety.

Impact IN 100 Years

The UPC’s 100-year journey — from early sanitation laws to an internationally recognized model code — has transformed public health standards:

It provides consistent, enforceable plumbing regulations across diverse regions.

- It supports innovation without compromising safety.

- It remains rooted in the same founding mission to protect the public’s health and safety through uniform, reliable plumbing systems.

Today, the UPC impacts nearly half of the world’s population, highlighting its remarkable growth and continued significance. The 2024 edition encompasses 484 pages; it is written in a double-column format; and is textbook-sized, reflecting its comprehensive scope. Due to this expansion, today’s edition is nowhere near the compact book that it was in 1945. Despite this substantial expansion, the advancements in technology now make the UPC readily accessible through the IAPMO Codes mobile app and the IAPMO Codes Development webpage, allowing users to conveniently reference the code on their mobile devices — bringing it back to their back pocket. I guess some things never change. Please join us at the IAPMO Annual Education and Business Conference to celebrate IAPMO’s 100th Anniversary.

Hugo Aguilar, P.E.

Last modified: February 19, 2026