FROM 1926 TO 2026: HOW PLUMBING GREW SAFER, SMARTER AND MORE DIVERSE OVER THE PAST 100 YEARS

IAPMO was created on May 17, 1926, by Los Angeles plumbing inspectors who wanted to write a model code for protecting the people they served from poor plumbing practices. While other organizations focused on creating construction or building standards, theirs was the first dedicated to developing plumbing and mechanical codes necessary for the advancement of modern plumbing systems.

Several years earlier, the United Association of Journeymen and Apprentices of the Plumbing and Pipe Fitting Industry of the United States and Canada, or as it is commonly known, the United Association or UA, became the first union to formalize apprenticeship training programs that taught trainees about codes like IAPMOs.

By doing so, the UA helped establish the plumbing profession as we know it today.

During the century following IAPMO’s founding the plumbing profession continued to evolve with almost every aspect of it changing, including who plumbers were, what they did, the tools and materials they used, and their training and education, wages, working conditions and regulatory environment. But the one thing that didn’t change, according to UA Director of Education and Training Ray Boyd, is that “plumbers have always been essential.”

“When you think about plumbers from 1926, they were charged with exactly the same thing they are today, which also happens to be the slogan of our industry: ‘The Plumber Protects the Health of the Nation.’ They do that by providing clean drinking water and proper sanitation. Just imagine what it would be like not having those things.”

| GETTY IMAGES

From Privies and Pots to the Porcelain Throne

While the role of clean water and proper sanitation in preventing disease was well known at the time, only one percent of American homes had indoor toilets during the early 1900s. Then came the Roaring Twenties when a wave of economic prosperity swept across the nation propelling an unprecedented boom in consumer spending and construction.

A pivotal period in the development of modern plumbing, the transition from outhouse to indoors was facilitated by research conducted by the U.S. Department if Commerce under the leadership of Herbert Hoover, who advocated putting plumbing in every home several years before he campaigned for president on the promise of putting a “chicken in every pot.”

As Americans migrated from rural communities into cities after World War II, bathrooms with a sink, toilet and bathtub became standard features. The availability of water mains also ended a reliance on wells, cisterns, streams and other sources of potable water for many households, so that by 1930, more than half of all urban homes had complete, indoor plumbing systems.

Once inside, plumbing continued to evolve as tank toilets came into common use and low profile versions with levers for flushing replaced overhead tanks drained by pulling a chain. Bathroom décor evolved as well, with colors going from a stark white previously considered more sanitary, to shades of green, pink, lavender and blue, as an expression of personal taste.

Kitchens underwent a makeover, too, with built-in sinks incorporating improved drainage systems that were less likely to clog supplanting free-standing versions. The installation of hot water heaters in more and more homes also meant that both hot and cold running water could be accessed on demand in kitchens, which made cooking and cleaning much easier.

In cities, population growth led to major building projects that included schools, shopping centers, industrial sites and public buildings, requiring municipalities to invest in comprehensive waste management along with water treatment and delivery systems on a much larger scale than ever before in order to protect public health and safety.

All of which created a burgeoning demand for plumbers, who unfortunately during these early years, Boyd says, were given “a bad rap in cartoons, TV shows, magazines and movies, that didn’t do justice to the skill, training and hard work that went into being one.”

The Development and Debunking of Stereotypes

“The stereotype of a plumber we were up against was that he was this person who came into your home, was overweight, smelled bad, and would charge too much to fix your toilet,” Boyd says. “You could also expect to see a certain part of his anatomy while he was working.”

UA Special Representative for Training and Outreach Laura Ceja attributes the persistence of this stereotype to “how plumbers are portrayed in the media” and describes it as “one of the most detrimental things” she has to overcome in recruiting for her organization, which is why much of what she does involves communicating what it’s really like to be a plumber.

“I got into plumbing 28 years ago because I stumbled across an ad in the newspaper,” Ceja recalls, “and for the longest time, awareness of it as a career was only by word-of-mouth. My goal today is to get the word out to everybody and let them know what a great opportunity the plumbing profession represents.”

The Changing Face of Plumbing

Although no demographic data is available, it’s probably realistic to assume that plumbers in the 1920s were predominantly white males since plumbing was considered unsuitable for women at the time and 89% of the country’s population identified as white.

Boyd notes that white males continued to dominate the profession throughout the ’40s and ’50s when “we were our own best-kept secret and there weren’t as many women and men of color in it like myself. However, the profession has matured and we’re more diverse now, which is partially a result of our recruitment efforts.”

Demographic Profile of Plumbers vs. the General Population

| U.S. | Plumbers | |

| White | 63.2% | 58.2% |

| Black or African American | 9.5% | 12.0% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 19.1% | 20.2% |

| Asia | 1.9% | 5.75% |

| Native American/ Alaskan | 1.1% | 1.0% |

| Male | 50.25% | 96.5% |

| Female | 49.5% | 3.5% |

While statistics show that plumbers today more closely mirror the composition of American society, the number of women in the profession still lags significantly behind. According to Ceja, “women started coming into the UA during WWII because men who were able-bodied were needed for the war effort and those who weren’t stayed behind to train the ‘Rosies,’” as they were called.

Boyd points out that at one time only men became plumbers because of the physical demands of the profession, but that’s no longer the case and he’s “seeing the number of women, particularly in project management and teaching, increasing at an encouraging rate.”

Ceja concurs, stating that “we’re doing things smarter, and plumbing is getting easier, so it’s no longer a dirty, dusty job that only men want to do. Which is how we’ve gotten more women interested in the profession and I think that’s only going to continue.”

The Only Thing Constant is Change

At the turn of the last century, plumbers had to lug cumbersome tools and heavy materials around, making their job labor intensive and somewhat true to the early stereotype.

But with electricity in half of all American homes by the mid-1920s, plumbers began using power tools such as drills and saws, followed by electric snakes, (also known as the Rotor-Rooters), in the 1930’s, and the electric pipe threader during the decade after that. All of which made their job faster, safer, and more efficient.

Since that time, the pace of innovation has accelerated and many of those same power tools are now cordless, making them lighter and more versatile. Hydro-jetting machines are also being utilized to clear stubborn clogs. Leak detection is aided by Infrared, thermal and ultrasonic leak detection systems. Compression fittings that are easy to connect and disconnect have replaced soldering and welding in many instances. And trenchless repair technology is being employed to break up old pipes and simultaneously replace them without having to dig them up.

Ceja reflects on the changes that have taken place just during her career. “The tools we have now are amazing,” she says. “I remember going from a plumb bob to a laser level practically overnight. It’s so amazing, it was like lighting a match in a cave.”

Boyd recalls a similar situation on job sites where he says, “you used to see rolls of blueprints lying around. Now you don’t see them anymore and everything is on a laptop where it’s more accessible and easier to change.”

Advances in materials have been just as dramatic, he notes. “We used to have lead distribution systems and lead working tools like ladles, packing and caulking irons, lead pots and furnaces that are all now part of our history.

“Because they’ve proven to be a significant health hazard, lead pipes are being replaced with ductile iron and copper or plastic, and that’s a process our members are heavily involved with in order to protect water supplies in our communities.”

Another area of plumbing that’s rapidly growing is sustainability. Starting with low-flow fixtures, sustainable solutions now include rainwater harvesting and greywater recycling systems that are increasingly being installed in residential and commercial buildings.

More recently, smart plumbing technologies have combined remote sensing capabilities with wi-fi applications to create what are called Internet of Things (IoT) devices capable of detecting, diagnosing and sometimes even repairing plumbing problems remotely.

These solutions include leak detection systems, smart water faucets, advanced water filtration systems and smart water heaters that are becoming more widely adopted with seemingly no limit to how other IoT plumbing devices may be used in the future.

In order to stay abreast of these developments Ceja says plumbers need “upskilling in order to stay marketable which, unless they’re in the UA, they have to pay for themselves.”

Formalizing Training and Education

Apprenticeship has always been “the basis of learning for being a plumber,” Ceja explains, and “our program is one of the best because we’ve had more than 100 years to refine it.”

The first of its kind, the UA’s formal apprentice program was established as a joint undertaking with the National Association of Plumbers in 1936. Recognized by the U.S. Department of Labor that provides oversight for it, this program requires a five-year apprenticeship with a minimum 720 hours of classroom instruction. Setting the standard for modern apprenticeship training, it has since served as a model for similar programs across the country.

“In the 1920s,” Ray says that, “whether you were union or non-union, you were probably still required to sit for an exam, sign up for an apprenticeship and get an apprenticeship license so you could learn under a licensed plumber.”

Licensure also became a requirement during the ’20s, with only a handful of states still not requiring it today. Plumbers had to pass an exam to receive a license before they could begin working as a journeyman plumber, with certification also necessary in many regions in order to verify their knowledge and experience in the trade.

Many aspiring plumbers also attend trade schools, while others go on to graduate from college like Ceja, who has a master’s degree. Those who do, she points out, are given a leg-up in the process by the UA apprenticeship program.

“Not only do they earn while they learn,” which is true for most apprenticeship programs, they also receive “45 credits for free they can apply toward getting a college degree,” Ceja says.

“Better yet,” Boyd adds, “unlike when you attend a four-year college, after you’ve completed our apprenticeship program, you’re walking away without any student loans you have to repay.”

Making Safety Job NO. 1

More than providing plumbers with “training and education, higher salaries and worker’s rights such as eight-hour days, paid holidays, health insurance and retirement benefits,” Boyd insists that “the number one thing unions have accomplished for plumbers is to improve safety.”

That’s because from the earliest days of plumbing as a profession, the health hazards associated with it were well-known. Whether it was from the risk of exposure to lead paint and plumbing systems, which was welldocumented, or the danger of dying from trenching accidents, which occurred all too often, plumbers needed protection.

Over the years, unions have provided that protection by advocating for stricter safety regulations; creating protocols for safer practices; developing training and apprenticeship programs that emphasized safety; devising continuing education programs to inform plumbers about the latest guidelines and equipment; negotiating with employers for safer working environments; and standing by members who spoke out about hazardous conditions.

For example, unions helped enact the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938 that set limits on working hours to help prevent accidents caused by fatigue. They were also influential in bringing about passage of the landmark Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA), which was signed into law by President Nixon in 1970.

Since then, OSHA has created standards for handling hazardous materials, using personal protective equipment (PPE) and implementing emergency procedures, among others. It has also created training courses for ensuring compliance with these standards and continues to be at the forefront of developments in improving workplace safety.

As a result of these and other actions taken by businesses, government entities and the plumbing industry itself, job-related deaths declined significantly between 1972 and 2020, with the incidence of injuries plummeting from 10.9 for every 100 workers to 2.4 during that same time period.

Which makes plumbing a far safer profession today than it ever was with the exception of one area that Boyd believes has been seriously neglected up until recently: mental health.

“If you look back at the ’20s, ’30s and ’40s, we weren’t concerned about mental health,” Boyd says. “We just wanted the biggest, strongest, most physically fit person for the job. Then about five years ago, we took a closer look at the industry and realized suicide and substance abuse were serious problems that needed to be addressed.”

Since then, the UA has lunched numerous initiatives to help workers cope with mental health concerns and aid in the prevention of suicide that include a Train the Trainer OSHA mental health compliance program for employers and a peer support network for its members called UA Pipe PALS (Peer Allies for Life Success).

“Today,” Boyd concludes, “we’re as engaged in our members mental health as much as we’re engaged in their physical health, and we’re proud of what we’re doing.”

While the proverbial plunger still has its place in the plumber’s toolbox, it’s no longer the mainstay of the plumber’s arsenal. | GETTY IMAGES

A Plethora of Plumbing Guidelines

Emerging alongside early efforts to improve worker safety were plumbing codes, standards and regulations which soon became a steady stream of guidelines governing almost every aspect of the plumbing profession. Ranging from training and education requirements to the installation of new products, they all shared the same purpose of protecting the health of the nation.

Timeline of U.S. Plumbing Guidelines 1906 – T h e American Society of Sanitary Engineering (ASSE) is formed to standardize plumbing and sanitary codes.

Creating a Pipeline of Professionals

While the focus on green and sustainable solutions and the integration of advanced technologies will most certainly continue to shape modern plumbing for the foreseeable future, the profession itself is headed for a period of uncertainty.

In 1920, it was estimated there were 206,714 plumbers and pipefitters in the United States, a number that more than doubled by 1930 due to the prosperity of the 1920s. By 2024, there were 736,000 people employed in this category with the demand for them projected to increase by 14 percent over the next 10 years, which is significantly higher than for other occupations.

Although this would seem to be a positive development, there is a problem. With the average age of plumbers skewing higher than it does for other workers, and the next generation less inclined to enter the trades, a shortfall of 550,000 plumbers is anticipated by 2035.

In response to this, unions, along with trade schools, community colleges, business owners, government entities and others, have redoubled their efforts to recruit, train and retain qualified individuals for the plumbing profession.

“We need plumbers, but everyone’s fishing from the same pond. So, we recruit and train heavily,” Boyd says, “and our doors are open to anyone who wants to be in this profession.”

As part of this process, Ceja says “my job is reaching out to career prep programs, high schools, counselors and organizations like the Association for Career and Technical Education, which is like a feeder organization for us, and providing them with recruitment and training materials along with connecting them with more than 300 training centers we’re affiliated with in the United States and Canada.

“We focus on everyone,” she explains, “but especially women and other under-represented groups that comprise our biggest potential source for plumbers in the future.”

All the Ingredients for a Satisfying Career

Ceja recalls the moment during an episode of Frasier where he realizes the plumber he’s hired makes more money than him. And while most plumbers don’t earn as much as a Harvard-educated psychiatrist with exclusive clientele and their own radio talk show, Boyd admits that “the wages are very good.”

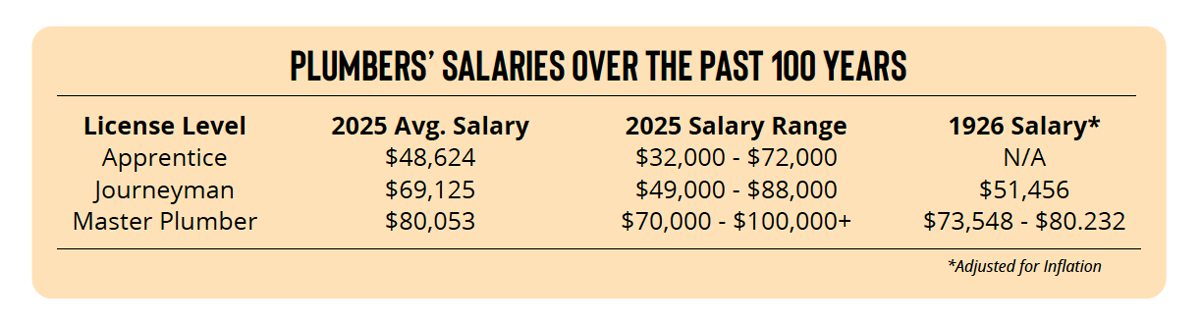

Plumbers earned an average of $63,231 in 2025, with individual salaries varying depending on the person’s license level, training and education, certification, type of job and job site, which state or city they work in, and whether or not they’re an independent contractor, belong to a union or have their own business. Of these, license level is probably the most significant factor contributing to differences in wages.

While comparable data isn’t available for the 1920s, a record of wages paid to the L.A. plumbing inspectors who created IAPMO found in the organization’s archives can be used as a snapshot for a comparison and suggest that, at least in this one example, plumbers’ salaries have generally kept up with or exceeded the rate of inflation over the past 100 years.

Job security is another benefit of being in the plumbing profession, Boyd suggests, “because we’re just as essential as doctors and nurses and firefighters. The pandemic showed us that.

“When they were erecting tents in parks and malls, they needed medical gas systems installed, and plumbers did that. Plumbers also installed drain waste piping and disposal systems for the temporary bathrooms that had to be set up. Our members were a vital part of that, too.”

Ceja concurs that plumbing is not only “pandemic proof,” it’s also “recession proof, which is something I push in recruitment. Jobs are not going to be outsourced to other countries or lost to AI.

“AI may help us work smarter,” she observes, “but it will never replace professional plumbers who do the work in the field or those who oversee it.”

Training and Outreach

Today’s plumbers also work in more places doing things that are far more challenging than repairing leaky faucets, unclogging drains or using a plunger to fix toilets.

Whether it’s working in residential, commercial or industry settings, designing and installing new systems or repairing, renovating or upgrading existing ones, there are now more choices than ever for an aspiring plumber to choose from as the foundation for a satisfying career.

After working in such a richly rewarding profession for more than 32 years, Boyd looks back on it and reflects: “I know what this career has meant in terms of what I’ve seen and what it’s done for me and my family, and I wouldn’t change a thing.”

Final Thoughts from the World’s Oldest Plumbers

Recognized by the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s oldest working plumbers, Lorne Figley of Saskatchewan and Ross Palermo of Pennsylvania would both undoubtedly agree with Boyd’s assessment of plumbing as a satisfying career.

When asked what kept him working for so long, Figley, who received the title in 2020 at the age of 92, said, “I’m addicted to learning so I’ve taken virtually hundreds of classes and think that’s what keeps you going.”

Palermo, who took over the title in November of last year and is still working after 74 years in a career that began in 1952, was more succinct in his response to the same question. “I just love plumbing,” he said. “I really do.”

If present trends continue, hopefully, there will be many others during the next 100 years who feel the same way.

Timeline of U.S. Plumbing Guidelines

1921 – President Hoover creates the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to set standards for building products and materials.

1921 – The UA becomes the first union to formalize apprenticeship training programs for plumbers.

1923 – Industry leaders meet to consider making fire hose couplings one of the first standardized plumbing products.

1926 – IAPMO is founded to develop plumbing codes for use in helping prevent unsafe plumbing practices.

1928 – The Hoover Code is issued and becomes the first official code for regulating plumbing systems.

1933 – The first National Standard Plumbing Code (NSPC) is released to guide compliance with health and safety requirements.

1936 – The UA and National Association of Plumbers introduce the first formal plumbing apprenticeship program.

1940 – Dr. Roy Hunter publishes his Commerce Dept. research, which is used to develop plumbing codes and standards.

1945 – IAPMO introduces the UPC as a model code to govern the installation and inspection of plumbing systems.

1970 – The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is set up to develop and enforce pollution control standards.

1971 – The Occupational Health and Safety Administration debuts to protect workers from workplace hazards.

1974 – The Safe Drinking Water Act is passed to set water quality standards and regulate public water systems.

1991 – The EPA releases the Lead and Copper Rule limiting allowable lead and copper content in water.

1992 – The Energy Policy Act sets water efficiency standards for maximum flush and flow rates for toilets and faucets.

2006 – The EPA begins its WaterSense Program to promote water conservation and the use of water-saving products.

2017 – Ownership of the NSPC is transferred to IAPMO and continues to be updated every three years.

Stephen Webb

Last modified: February 19, 2026